- Home

- Louis G. Gruntz

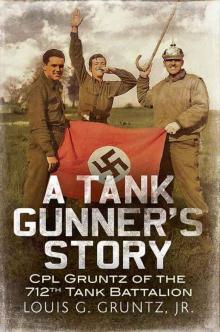

A Tank Gunner's Story: Gunner Gruntz of the 712th Tank Battalion Page 2

A Tank Gunner's Story: Gunner Gruntz of the 712th Tank Battalion Read online

Page 2

I was always fascinated by the fact that the small light source in front of the giant parabolic mirror produced such an intense beam of light and how these white shafts of light extended far into to the dark heavens and danced across the skies. During all of these occasions, however, Dad never mentioned to me the military uses for which these lights were originally built.

While Dad and Mom would enjoy this escape from daily life, being an only child, I had a different perspective on our weekend sojourns. Although I usually enjoyed our weekends once in Waveland, I often dreaded these trips as the weekends drew near. Going to Mississippi meant my friends were back home in Louisiana, to make matters worse, there was very poor TV reception in Waveland. Additionally, in those days before the interstate highway system had been constructed, US Highway 90 was the only road that led eastward out of the city, it was a long two-hour ride in our 1952 Ford Sedan between our home the western side of New Orleans and our weekend home in Waveland.

Every child has an imagination, it is said to be an important part of a child’s development. I was certainly no different in that respect from other children. I suppose I compensated for the lack of friends and TV in Mississippi by kicking my imagination into high gear to pass the time away. This process began with the two-hour drive.

Our trek took us through the city streets and then past the Industrial Canal in eastern New Orleans, near one of Higgins’ shipyards. I recall Dad speaking of his pre-war work in the nearby shipyards, but never any mention of the war itself

Once past the eastern New Orleans suburbs, the road narrowed to two lanes through the narrow strait of marsh and swamp that separates Lake Pontchartrain from Lake Borgne and the Gulf of Mexico. The route took us past two nineteenth century forts, Fort Pike and Fort Macomb, erected on the Rigolets Pass and Chef Menteur Pass respectively. These large brick fortifications were erected on these two waterways, connecting Lake Pontchartrain and the Gulf of Mexico, to prevent enemy forces from entering Lake Pontchartrain and launching a rear attack on New Orleans. Fort Macomb was closed to the public and in a deteriorating condition. Fort Pike, on the other hand, was maintained by the state park service. A two hour drive was boring for any child, I was no exception and although Mom and Dad were anxious to reach our final destination, on one or two occasions we stopped and toured Fort Pike. My imagination went wild from the moment we crossed the bridge across the moat into the entrance of the fort – I was immediately transported back into history. Whether peering from one of the gun ports or overlooking the adjacent waterways from the upper parapets I was repelling an imaginary enemy attacking my home town. Despite the resemblance between Fort Pike and some of the forts that comprised the Maginot Line surrounding the French city of Metz where Dad fought, there was no mention of World War II. Perhaps it was still too fresh in Dad’s memory and he had not yet considered it as achieving the status of ‘history’. To Dad, World War II was still merely old news.

Once past the Rigolets and into St Tammany Parish, Highway 90 enters the Honey Island swamp along the narrow ridge that was an ancient Indian trail and then utilized by French and Spanish settlers to travel between Mobile and New Orleans in the 1700s. It is still known as the Old Spanish Trail. There was not a single thing along this foreboding and desolate stretch of road with the exception of the White Kitchen Restaurant built in 1933 at the junction of US Highway 190 and US Highway 90. It was the midway point between New Orleans and the Mississippi Gulf Coast and was open 24 hours a day for weary travelers. Its landmark sign was an Indian Brave kneeling and holding a skewered fowl over a campfire. We occasionally stopped at the White Kitchen because no matter how much Mom and Dad exhorted me to go to the bathroom before we left home, that two-hour ride was just too long.

Exiting the Honey Island Swamp as we crossed the East Pearl River into Mississippi, we began to see a few semblances of civilization, but we still had another half hour drive through the pine woods of southern Mississippi to reach our weekend home. I would imagine an invisible enemy lurking behind every tree ready to attack as our car, the lead vehicle in an imaginary military convoy, proceeded along the highway.

Summers in Waveland also meant swimming at the beach. My imagination would transform the beaches of the Mississippi Gulf Coast into the D-Day beaches of Normandy; as I waded ashore in waist deep water, the imaginary bullets whizzed past me striking the water. Upon reaching the shore, I would zig-zag across the sand avoiding the enemy fire from an imaginary machine gun until I safely reached the three foot high concrete seawall.

My youthful imagination was fed by the movie and TV images of that era. As I look back on those films of my childhood, I realize how much those movies of the ’50s and ’60s portrayed a sanitized and glamorized image of warfare. When soldiers were killed in action in the movies, death was painless and instantaneous with one bullet. There was no blood, no maiming or prolonged suffering depicted in those films. I did not realize until my journey with Dad, just how much these early movies not only shaped, but shaded my perception of war and combat.

War had become a game to us Baby Boomers. During one school picnic all the boys played an early version of today’s paint ball. Armed with water pistols loaded with red Kool-Aid, we separated into two armies and entered the wooded area of the camp grounds and began our war. A red stain on our T-shirt indicated that we had been wounded by the opposing side and we were out of the game, we had to return to the main picnic camp site. The group with the most unstained shirts at the end of the game was declared the winner of the war.

In 1957, my grandfather, Ernest Casteix, suffered a debilitating stroke that left him partially paralyzed. The father-in-law/son-in-law business was dissolved and the dry cleaning business fell solely on Dad’s shoulders.

During this period, Dad also began several real estate ventures on the side that proved quite successful. We sold the Higgins Hut on Merritt Street and purchased an older sturdier residence on Jefferson Davis Boulevard in Waveland. Our new vacation home included a large tract of land to the rear. Dad had a road installed, subdivided the tract into lots and sold them to other New Orleanians seeking a weekend or vacation retreat.

As a sole proprietor, Dad’s business began to prosper. He remodeled and modernized the cleaners. Dad was determined that I would not be deprived of any educational opportunities. With their additional income, Mom and Dad transferred me from public school to St Agnes Parochial School.

One night in the late ’50s we had a special dinner guest. My mother was scurrying around getting the good china, polishing the silver, and setting the table in our dining room. It was the first time I ever recall that we would be using it for dinner rather than show. The guest that night was Joe Roush, one of Dad’s friends from the 712th Tank Battalion. Joe lived in Oklahoma but was in New Orleans on business for several days.

At no time during the night did either Joe or my father talk about their war experiences. The closest thing discussed was Joe’s desire to have a reunion of the soldiers from B Company of the 712th Tank Battalion and to regain contact with all of their Army buddies. In 1962, Joe eventually published an inaugural newsletter and began making plans for a reunion of B Company veterans in Milwaukee, scheduled for 1964.

Meanwhile as I entered my teens, my early childhood perceptions of war as a glamorous adventure were reinforced by the epic films of the 1960s. Although death was depicted, there was no blood or gore or agonizing death scenes in such films as The Longest Day, The Guns of Navarone, Bridge on the River Kwai, The Great Escape, Von Ryan’s Express, The Dirty Dozen, and by TV programs, such as Combat and The Gallant Men. The entertainment industry further skewed baby boomers’ perceptions of war by making comedies such as McHale’s Navy and Hogan’s Heroes.

I no longer needed to ask Dad anything about the war. After all, I had been granted the same omniscience granted to all teenagers; these films and TV series merely reinforced my misconceptions.

My high school years, from 1961 to 1965, coincided with the twentieth

anniversary dates of America’s involvement in World War II; it also marked the centennial of the Civil War. I continued my fascination with this era in American and Louisiana history. I drew a confederate flag on one of my notebooks with the initials CSA. Mom was mortified that I had adorned my notebook with such initials. She had not realized that I had intended the CSA to be an abbreviation of Confederate States of America. She explained that CSA was the initials for a derogatory name that the residents called our neighborhood. With its history of being dairy farms and housing cattle barns, many of the people living in our area referred to Brooklyn Avenue as Cow Shit Alley. That revelation tarnished the allure those initials had for me.

During the early ’60s, there were no memorial tributes like today, I do not recall any specific news or media coverage of any of the World War II events, with perhaps the brief news announcements commemorating Pearl Harbor. Americans became fixated on space exploration and our newest heroes – the Astronauts. We looked to the future, not the past. I imagine Dad welcomed the respite from my juvenile questions about World War II.

I entered Jesuit High of New Orleans, which had the very first junior ROTC program in the country. The entire student body wore khaki uniforms in the early fall and late spring and winter Marine wool uniforms from December through March. Close order drill was substituted for physical education twice a week. The Jesuit priests believed close order drill was an important method of instilling discipline as well as an important method of teaching teens the leadership skills necessary for adult life. With Dad in the dry cleaning business, my uniforms had crisp military creases on a daily basis. Although Dad had given me some tips on drill, there was still never any discussions about his combat experience.

Then in November 1963 President John F. Kennedy was assassinated. The only reference to World War II that I recall from that period was Kennedy’s heroics on PT 109 in the Pacific.

1964 marked the twentieth anniversary of D-Day. I was 17 years old and not particularly interested in hearing Dad’s stories about World War II, after all, I had learned everything there was to know from the movies and TV during my early teens. In August of that year, my parents and I were traveling to Milwaukee for the first reunion of B Company of the 712th Tank Battalion. As boring as that may sound for a seventeen year old, I didn’t mind going. Having only rarely traveled beyond 100 miles of New Orleans, this trip seemed adventurous and certainly the other veterans of the 712th would have kids my age. We traveled to and from Milwaukee by train. Despite being summer, the Milwaukee weather seemed cool to us thin blooded southerners from New Orleans.

Dad quickly renewed friendships with his old wartime comrades and Mom quickly formed new friendships with their wives. I do not recall the men talking of their war experiences during this reunion, instead they talked about what had transpired in their lives in the twenty years since the end of the war – their jobs and professions, their hobbies, and their families.

The younger generation kept to ourselves and were not interested in the Allied invasion of Europe. Our interest was in the British invasion of America… by the Beatles and the other British rock groups. After the reunion we traveled home again on the Illinois Central train that has since become legendary in song, ‘City of New Orleans’.

Curiously, the most outstanding memory of this reunion, occurred one morning at breakfast in the diner in the Milwaukee train station. When I told the waitress I wanted an order of grits for breakfast, she said “Grits! What is that?” I had forgotten I was north of the Mason-Dixon line.

By 1965, Baby Boomers were entering college. In the fall of 1965, I enrolled in the School of Engineering at Tulane University. College life is a period of new found freedoms, and my generation pushed those freedoms to the limits. During the latter part of the 1960s, neither I nor probably any other early Baby Boomer had any interest in hearing about our parents’ military experiences. Furthermore, having just completed four years of military style discipline and drill in high school, I wasn’t interested in ROTC at Tulane, I declined all the recruiting overtures.

The second reunion for the 712th was scheduled for the summer of 1967 in New Orleans; this reunion included all of the 712th Tank Battalion veterans, not just B Company. Being in our hometown, Dad chaired the reunion. After the 1967 reunion the bonds of friendship that had been rekindled became even stronger, many of these veterans visited my parents in the succeeding years and vice versa. They were John and Rose Ockenga, from Ohio, the 712th cluster from Wisconsin – Bob and Arlone Kellner, Bob and Kathleen Gaulke, Al and Lucy Helland, Ted and Clara Ballman, Wally and June Kubert, Orin and Caren Bourdo. From other locales were Ed and Irene Swierczyk, Ziggy and Regina Kaminski, and Chester and Margaret Martin from Pennsylvania, Jim and Emma Armstrong and John and Gladys Essenburg from Michigan, Juel and Billye Winfrey from Oklahoma and Roy and Eva Bardo from Kansas City.

At the time of the1967 reunion, I was going steady with my future wife, Cora. She came to the reunion and we both helped with the behind the scene details that an event like this requires, such as registration of attendees, making name tags, and the like. If any of these old army buddies were telling any war stories, I didn’t hear them, Cora and I were only interested in spending time together.

By 1967, the conflict in Vietnam had grown significantly from a small amount of military advisors to over 365,000 American troops. Some of the children of World War II veterans were learning firsthand the reality of war. The rest of us witnessed the fighting taking place in Southeast Asia by extensive coverage of the war in the nightly newscast on TV. It was also a time when we Baby Boomers began to question authority, and protests began against the Vietnam conflict. While some from my generation were fighting and dying in Vietnam, others were protesting in the streets and on campuses across this county. For still others, like myself, the events of the era seemed to bypass us. Always conscious of the possibility of eventually being drafted, I received a student deferment from the draft and throughout my undergraduate studies concerns about Vietnam were avoided.

Tulane University was not immune to the anti-war protests, but they were relatively small and generally limited to a small group of students. The arch-conservative student body of the engineering schools generally paid little attention to these demonstrations as we were buried in our books.

The typical engineering student of the ’60s had short hair, horned rim glasses, and carried a slide rule to class. Admittedly, I fit the stereotyped image of such an engineering student. The stress of studying was offset by my membership in Pi Kappa Alpha Fraternity. The global politics and the Vietnam war were not in the forefront of my daily concerns.

Cora and I married during the summer before my senior year in 1968. After graduation in May of 1969, I was employed as a mechanical engineer in a local chemical industry. Life was great and in October of 1969 my first son, Louie, was born.

Working as an engineer during the day, I attended Loyola Law School’s evening division. My penchant for expanding my education was instilled within me at an early age by my father. He would always tell me, “It is easier to earn a living with your brain than it is to earn it with your brawn.” I am sure his attitude was borne out of the educational opportunities denied to him as a youth.

When I eventually received a draft notice in early 1970, I went for my induction physical examination. During my physical, the doctor discovered a minor medical problem. I received a medical deferment and, consequently, any concerns I had about combat vanished. Furthermore, my second son, Cory, was born in 1970 and my thoughts were concentrated on my job and earning a living. I never had to give much thought about the reality of combat. My perception and opinion on war remained stagnated in the cinematic images of World War II that I acquired in my youth and were unaffected by the realities of the late 1960s and early 1970s in southeast Asia.

It was also around that time, the movie Patton, starring George C. Scott, was released. This is when I first learned from Dad that the 712th Tank Battalion was pa

rt of the Third Army under the command of Gen. George S. Patton Jr. Dad saw the movie and recalled many of the areas and the events that were depicted in the movie. But he still refrained from initiating any detailed discussion regarding his own personal wartime experiences.

During the scene involving Patton’s prayer before the Battle of the Bulge, Dad said the prayer actually existed and copies of it were distributed to all members of the Third Army; Dad’s copy was tucked away someplace in his box of memorabilia in his closet.

This film, like those produced in the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s had a patriotic theme, and had the effect of reinforcing many of my misconceptions of actual combat. This was a golden opportunity for me to learn more about Dad’s wartime experiences, but I let it slip by. The rigors of working as an engineer during the day and attending law school at night made spare time a commodity that I could only spend on my own personal Paper Chase.2

In 1974, the 30th anniversary of D-Day, I had just finished law school and was about to embark on a legal career. The last thing on my mind during those days was to sit down with my father and discuss his war experiences. During this period, Dad joined and became active in the American Legion. It was also during this period that a then unknown professor from the University of New Orleans was soliciting World War II veterans in the New Orleans area for interviews regarding their experiences during the war. Dad declined these invitations to talk about the war, later stating that he did not want to tell a stranger the stories he had kept to himself for so long. The university professor was none other than Stephen E. Ambrose.

In 1982, Mom and Dad took a trip to Europe and visited many of the locations where Dad had been during the war. Although I would have enjoyed going on that the trip, such a vacation at that time was simply out of the question. I was employed as an Assistant Parish Attorney for Jefferson Parish, my daughter Rochelle, was born in 1976, and Cora was expecting our fourth child, David. Needless to say, I was busy with the affairs of my family.

A Tank Gunner's Story: Gunner Gruntz of the 712th Tank Battalion

A Tank Gunner's Story: Gunner Gruntz of the 712th Tank Battalion